Hypercommunication

24/11/2025

Introduction

This essay argues that hypercommunication, as delivered by current sociotechnological systems, degrades our capacity for empathy. In examining everyday conversation, the influence of big data, and specific case studies like Altena, Germany, where the behaviour of residents in the town was directly affected by misinformation spread online(Taub and Fisher, 2018), this essay aims to understand and remedy the effects of Hypercommunication.

Hypercommunication

Hypercommunication can be defined as excessive and constant inbound and outbound communication, largely facilitated by widespread sociotechnological systems such as social media networks (Begg, 2023). 68% of the world's total population are mobile phone users, and just under 60% are now active on social media (Kemp, 2023). Social media apps increasingly become engineered to game and hold our attention in the form of features such as AI content predictive algorithms – Algorithms that try to predict what a user might want to see next to keep them using the platform (Grosser, 2020). These serve the purpose of instilling addictive tendencies and artificial compulsions in human users (Goldman, 2021).

In the advent of the mobile phone; traditional, synchronous and unmediated conversations have been displaced by asynchronous and mediated communication (Begg, 2023). Studies suggest that daily life without offline conversation can make us less empathetic, less creative and less fulfilled; researchers note a correlation between online messaging and decreased levels of intrapersonal connection (Turkle, 2016). This shift from physical conversation to online communication has been meticulously designed on behalf of social media companies as agents of neoliberal technocapitalism, making us tend more towards conformity by means of constant influence and suggestion; commodifying and exploiting our everyday actions and effectively colonising our everyday existence (Han, 2017; Begg, 2023).

Life without Conversation

People are now using more social media than ever before, thereby increasing the number of channels that an individual can use to communicate and the amount that people can communicate via text-based mediums and posts (Begg, 2023; Kemp, 2023). For many, a litany of sentiments can be encapsulated in the phrase ‘I’d rather text than talk’ (Turkle, 2016). Everyday conversation consists of many verbal and nonverbal cues and yet people across generations are expressing that speaking face-to-face can feel overwhelming because ‘you can’t control what you’re going to say’ (Turkle, 2016; Segal et al., 2018). This preference for asynchronous communication stems from the desire for control and convenience; sending carefully composed and edited text messages feels like a ‘solution’ to conversation, in which awkwardness and mistakes are less likely to happen. Responses can be edited to get them ‘right’ every time – accompanied by an increased anxiety about the spontaneity and unpredictability inherent in real-time conversation (Turkle, 2016).

When technology is used incessantly like this, it creates two distinct selves: the ‘real-world self’ and the ‘digital self’. The digital self can be a version of the theory of the ‘ideal’ self, representing who the user is and who they want to be (Boyatzis and Dhar, 2022). Social media creates opportunities for self-curation, which can create more opportunity for incongruence between identities (Turkle, 2016; Boyatzis and Dhar, 2022). As the gap between these two selves increase; the level of satisfaction within a person’s interpersonal relationships decreases, as they may feel more drawn to the curated interactions performed by their digital ideal self (Begg, 2023). Asynchronous communication reduces the natural flow of conversation to a simple exchange of information, where conversation can become less learning-centred, and more information-centred (Begg, 2023). In turn, essential, everyday conversation can become replaced by hypercommunication, which in this instance refers to a constant influx of signs, symbols, notifications and simple strings of language; removing all the wonder and desire from communication by becoming isolated words (Begg, 2023).

Empathy is something that is learned and practiced through everyday conversation, in which we come to see each other and listen and understand what the other is saying, as well as seeing the other’s emotions and body language – the benefits of this are lost when we turn away from conversation and towards our devices. Hence, our everyday capacity for empathy is degraded when we lose these empathic parts of conversation (Turkle, 2016).

Big Data

Many social media companies in network culture, namely Meta, benefit from monopolizing communication channels (Leetaru, 2018; Begg, 2023). The method of this is the feedback loop of information between the platform and the user; users seek information and entertainment, and social media platforms provide an endlessly tailored and optimised response. In turn, the platform records the user’s every action, using an algorithm to predict what the user might want to see next to keep that user on the platform; thus continuing to scroll, like and post (Grosser, 2020). Meta’s account numbers are only ‘people’ when the context is about extracting monetizable behaviours from them; the rest of the time they are dehumanized through the term ‘user’ to remind us that we are merely datapoints produced by our activity, not real human beings whose lives are being exploited, monetized and colonised for its benefit (Leetaru, 2018). In network culture, the vehicle of the delivery of this aspect of hypercommunication is the software itself, as the software is endlessly optimised for engagement, evaluating every interface design decision for its ability to increase user time on site. Their profit is obtained not from genuine human conversation and connection but from the value of data produced from the user under surveillance capitalism, which is the endless text, symbols and content itself (Grosser, 2020; Begg, 2023). This dynamic undermines the practice of empathy by prioritizing self-curation; people perform as their digital ideal self when connecting to each other and constantly curate their self-image for public consumption through their texts and posts (Turkle, 2016).

Likes, follows and messages can be a primary method of achieving perceived social success or failure instead of narrative feedback from everyday conversation outside the platform (Lovink and Grosser, 2020). This exposure to hypercommunication is the method of conformity and unified consumption under capitalism through its subtle and overt influence over our everyday decision making (Begg, 2023). In turn, a user can be recommended to buy products based on the information about their digital ideal self that they give to the platform by interacting with it and can be pushed to buy for their ideal self instead of their real self (Fivelsdal and Fossberg, 2022). This fuels a cycle of ‘selves’ as commodities and marketing identities, which are prioritised over self-acceptance and conversation in the real world (Han, 2017). Additionally, the fast-paced nature of hypercommunication discourages the reflection and emotional engagement necessary for cultivating empathy, replacing it with surface-level interactions that prioritize quantity over quality. As users increasingly interact through screens, emotional detachment becomes normalized, and the ability to interpret non-verbal cues - an essential component of empathy - is diminished (Turkle, 2016).

Case Study: Altena, Germany

In 2018, the suburban town of Altena, Germany, witnessed a series of hate crimes targeting refugees, including an incident involving a young firefighter trainee named Dirk Denkhaus. Despite never previously displaying overt anti-refugee sentiment, Denkhaus broke into the attic of a refugee group house and attempted to set it on fire (Taub and Fisher, 2018). Research by Karsten Müller and Carlo Schwarz of the University of Warwick has revealed a strong correlation between Facebook usage and anti-refugee violence in German small towns (Muller and Schwarz, 2018). Their study analysed 3,335 anti-refugee attacks across Germany over two years – checking for any variables of any relevance such as wealth inequality, far-right political support, refugee populations over time and historical hate crime levels. The key finding was that towns with above-average Facebook use experienced a 50% increase in anti-refugee attacks, irrespective of other factors (Muller and Schwarz, 2018).

AI content-predictive algorithms must constantly push more and more provocative content to keep the user engaged and scrolling, which is sometimes known as ‘doomscrolling’ (Grosser, 2020).

On social media, news becomes the commodified spectacle in which a completely new worldview has originated from the hyperreal information constantly presented to us by hypercommunication (Debord, 2013). In the network society, reality can be warped into hyperreality where any constructed situation projected by screens is objective truth; through algorithms, social media constantly places inflammatory and mind-bending information in front of viewers to distract and hold their attention (Begg, 2023). Humans are predisposed to react to negative news (Grosser, 2020). Combining the natural instinct to react to bad news with platforms that prioritise user engagement can create a situation where users are exposed to misinformation and disinformation (Grosser, 2020). A Facebook user in Altena might conclude that their neighbours were broadly hostile to refugees –Facebook had created a virtual reality in which anti-refugee sentiment was widespread in the town (Muller and Schwarz, 2018). Users were repeatedly encountering racist vitriol on local pages, in contrast with Altena’s public spaces, where people wave warmly to refugee families (Taub and Fisher, 2018).

Empathy does not prevail in an environment of disinformation; in which refugees are the subject of large scale fearmongering and hate campaigns (Taub and Fisher, 2018). People instinctively conform to what they have been led to believe their community’s belief to be (Paluck, Shepherd and Aronow, 2016). Prosecutors on Denkhaus’ case, after seizing his phone, had argued that Mr. Denkhaus had isolated himself in an online world of fear and anger that helped lead him to violence (Taub and Fisher, 2018).

Remedial actions

In a neoliberal technocapitalistic network society, technology causes the individual to crave constant dopamine hits and instant gratification at scale leading to an itch for constant occupation and an aversion to stillness and intrapersonal connection (Begg, 2023). This creates an endless feedback loop of the spectacular through habit forming technologies, where users are constantly exposed to a reward cycle of ‘Cue’, ‘Action’, ‘Reward’ and ‘Investment’ cycles (Eyal, 2012). This is usually leveraged to further insert mediated experiences with technology into our daily life (Begg, 2023). Even in futile attempts to un-mediate our everyday existence, the cell phone seems to seduce its way back into most situations in some form. With this, constant transparency and the frequency of asynchronous communication leads to conscious and subconscious perceptions of others based on the digital ideal self (Begg, 2023).

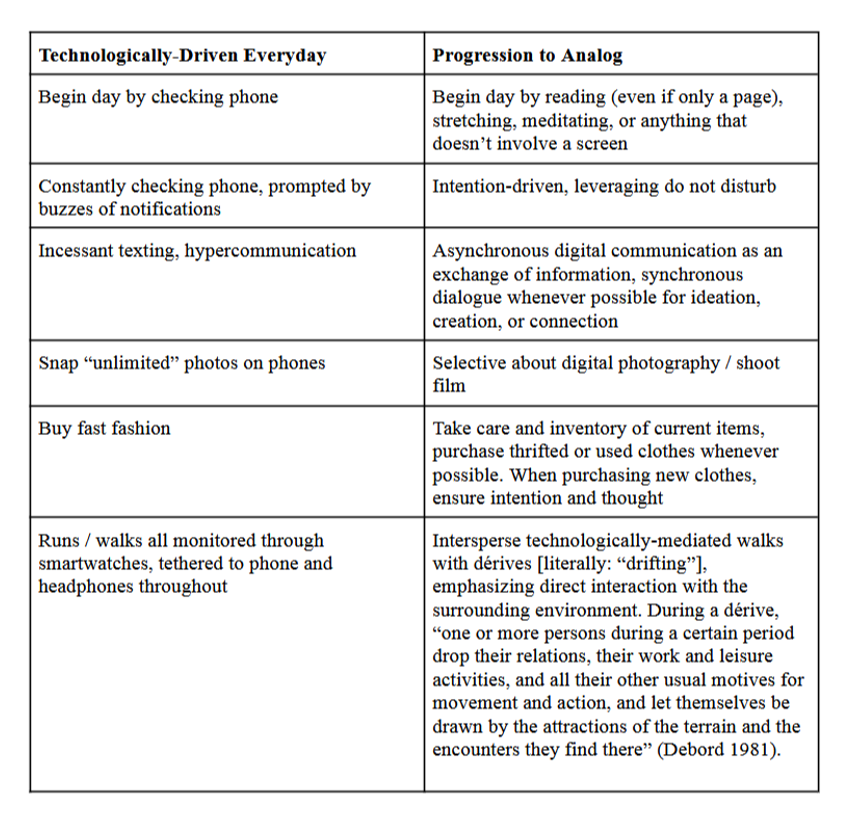

Begg writes that if there is a way to move away from this perilous, doomed existence, it is through a ‘progression to analogue’ which returns charm and attention to communication. Through intentional approaches to daily interaction, we can actionably improve our wellbeing and capacity for empathy and grow away from hypercommunication, and embrace a life of spontaneous creativity and learning (Figure 1).

Figure 1

In this model, technology can become a tool and not a crutch (Begg, 2023). By choosing to seek stimulation from our environment instead of our devices, we can rediscover the act of discovery, the art of conversation, and increase our empathetic and conversational skills with others through practice (Turkle, 2016). When screentime and phones were removed from a school environment, the children communicated face to face and they are engaged with each other, the faculty, and themselves. They read books, did art projects and played games outside (Jacobs, 2023). This instance serves as an example of how we can replace the time we spend engaging with hypercommunication and embrace off-screen interaction with our peers and surroundings, prioritising creativity and spontaneity through things like hobbies and conversation (Turkle, 2016).

Conclusion

Hypercommunication, as perpetuated by sociotechnological systems like social media, significantly diminishes our capacity for empathy. Real time, face-to-face conversations are displaced by asynchronous communication in which there is no wonder or desire. The commodification of information and the amplification of inflammatory content by AI content predictive algorithms led to real-world consequences such as hate crimes, by consequence of a network society that diminishes our capacity for empathy. This facet of the network society, driven by neoliberal technocapitalism, prioritizes engagement and profit over genuine human connection.

In order to take control of this as an individual, it is crucial to adapt intentionality and make choices to communicate in a way that prioritizes authenticity, spontaneity, and empathy. Begg’s ‘Progression to analogue’ can help us rediscover the wonder in conversation and our environment –moving towards an existence that resists hijacking of our attention and restores the human values of empathy, creativity, and connection that are essential for a healthy and fulfilled network society.

References

Begg, C. (2023) ‘Everyday Conversation: The Effect of Asynchronous Communication and Hypercommunication on Daily Interaction and Sociotechnical Systems’. figshare, p. 475841 Bytes. Available at: https://doi.org/10.6084/M9.FIGSHARE.24103758.

Boyatzis, R. and Dhar, U. (2022) ‘Dynamics of the ideal self’, Journal of Management Development, 41(1), pp. 1–9. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1108/JMD-09-2021-0247.

Debord, G. (2013) The Society of the spectacle. Paperbound edition. Berkeley, CA: Bureau of Public Secrets.

Eyal, N. (2012) The Hooked Model: How to Manufacture Desire in 4 Steps, Nir and Far. Available at: https://www.nirandfar.com/how-to-manufacture-desire/ (Accessed: 24 January 2025).

Fivelsdal, L.K. and Fossberg, S. (2022) ‘Who Am I Really? Concept of the Self, Body Image, and Buying Behavior’.

Goldman, B. (2021) ‘Addictive potential of social media, explained’, Scope, 29 October. Available at: https://scopeblog.stanford.edu/2021/10/29/addictive-potential-of-social-media-explained/ (Accessed: 3 January 2025).

Grosser, B. (2020) On Reading and Being Read in the Pandemic: Software, Interface, and The Endless Doomscroller – electronic book review. Available at: https://electronicbookreview.com/essay/on-reading-and-being-read-in-the-pandemic-software-interface-and-the-endless-doomscroller/ (Accessed: 1 January 2025).

Han, B.-C. (2017) Psychopolitics: Neoliberalism and New Technologies of Power. Translated by E. Butler. London New York: Verso.

Jacobs, D. (2023) ‘Taking an Intentional Approach to Technology’, Childhood Education, 99(4), pp. 72–75. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/00094056.2023.2232285.

Kemp (2023) Digital 2023: Global Overview Report, DataReportal – Global Digital Insights. Available at: https://datareportal.com/reports/digital-2023-global-overview-report (Accessed: 2 January 2025).

Leetaru, K. (2018) What Does It Mean For Social Media Platforms To ‘Sell’ Our Data?, Forbes. Available at: https://www.forbes.com/sites/kalevleetaru/2018/12/15/what-does-it-mean-for-social-media-platforms-to-sell-our-data/ (Accessed: 23 January 2025).

Lovink, G. and Grosser, B. (2020) ‘Ben Grosser-Geert Lovink Dialogue on Media Art in the Age of Platform Capitalism’, Institute of Network Cultures, 23 April. Available at: https://networkcultures.org/geert/2020/04/23/ben-grosser-geert-lovink/.

Muller, K. and Schwarz, C. (2018) ‘Fanning the Flames of Hate: Social Media and Hate Crime’.

Paluck, E.L., Shepherd, H. and Aronow, P.M. (2016) ‘Changing climates of conflict: A social network experiment in 56 schools’, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 113(3), pp. 566–571. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1514483113.

Segal, J. et al. (2018) ‘Body Language and Nonverbal Communication’. Available at: https://www.helpguide.org/relationships/communication/nonverbal-communication (Accessed: 19 January 2025).

Taub, A. and Fisher, M. (2018) ‘Facebook Fueled Anti-Refugee Attacks in Germany, New Research Suggests’, The New York Times, 21 August. Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2018/08/21/world/europe/facebook-refugee-attacks-germany.html (Accessed: 25 January 2025).

Turkle, S. (2016) Reclaiming Conversation: The Power of Talk in a Digital Age. Reprint edition. New York: Penguin Publishing Group.